The Aims, Objectives and Research Design for the Heslerton Parish Project

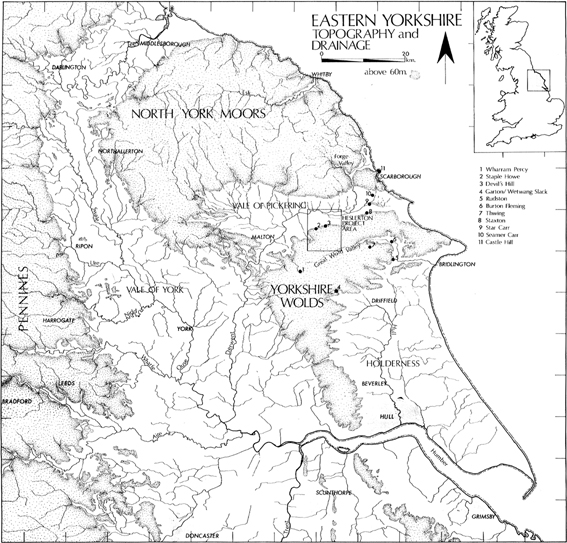

There are certain regions of the British Isles which have long been recognized

as areas of primary archaeological importance. One of these, Eastern Yorkshire,

comprises three distinct geomorphological areas; the North Yorkshire Moors,

the Vale of Pickering and the Yorkshire Wolds. Archaeological work has

been in progress in the area since the late 18th Century and the work of

pioneers such as Greenwell and Mortimer has been fundamental in developing

the basic corpus of information which now forms an essential element in

the literature of prehistoric studies. Subsequent work by Brewster, Manby

and others has developed this body of information and clearly emphasized

the traditional view of the area's importance, particularly in the field

of British Prehistory.

Figure 1 Location of the Parish Project area (after

Powlesland et al, Arch J, 143 (1986) page 54)

The Heslerton Parish Project was set up in 1980 to form

the framework for major archaeological work, both rescue and research,

into which the evolution of the landscape of Eastern Yorkshire, an area

of established national significance, could be placed. At this time, references

to assessments of the prehistoric and Anglian evidence emphasized the sepulchral

bias: Longworth (1961), Simpson (1968), Clarke (1970), Cunliffe (1974)

and Rahtz, Dickinson, Watts (1980). It was also clear from statements made

by the Prehistoric Society in 1978, that a number of archaeological bodies

were developing a "landscape strategy". They stated that it was vital "...

to establish as wide a range as is possible of environmental, economic,

chronological and social evidence." The general statement was qualified

by a number of conditions which should be met in the selection of "nationally

important projects". These included sites with well preserved organic material,

sites sealed beneath alluvial, colluvial or aeolian deposits, sites where

environmental, economic or structural evidence is preserved and settlement

or cemetery sites where total or substantial excavation is possible. Work

carried out at Sherburn and West Heslerton had indicated that most if not

all of those conditions could be satisfied by the parishes along the southern

edge of the Vale, while suitable sites satisfying the wide range of conditions

must be rare on either the Wolds or the Moors.

Heslerton: A sample of The Yorkshire Landscape

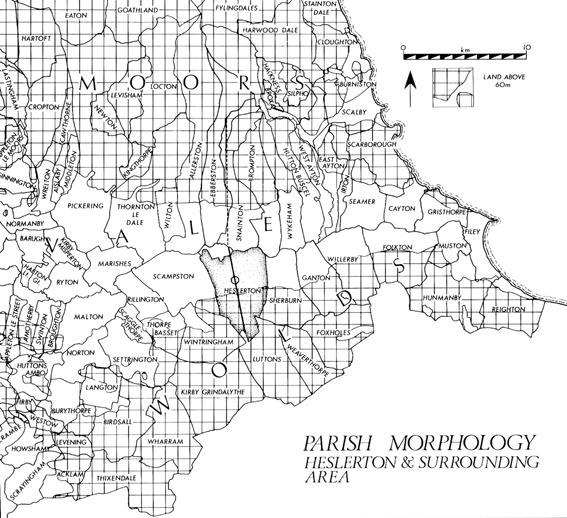

Figure 2 Parish morphology in the Project area

(after Powlesland et al, Arch J, 143 (1986) page 56)

There has been much discussion relating to the division

of the English landscape into parishes. It should therefore suffice to

say that the parish structure developed at an early date and, more importantly,

that it developed on an economic base which gave the population access

to a wide range of environmental and economic zones. In the Vale of Pickering

there is a high degree of uniformity in the morphology of the parishes

both to the north and to the south of the River Derwent. All of those within

each group, except the small monastic parish of Yedingham which controls

the highest navigable point of the Derwent, cover roughly equal areas of

high and low ground. Each parish contains the complete range of available

micro-environments and thus any parish could provide a widely relevant

sample which could be used to create a model for the area as a whole. The

nodal position of Heslerton, the extent of past and current work in the

parish and the presence of a major archaeological threat in the form of

a sand quarry cutting across a broad zone of stratified deposits, all led

to the selection of Heslerton parish as a representative sample of the

landscape running from the banks of the River Derwent to the top of the

Wolds.

Past Work in the Area

The distribution of known archaeological remains at the outset

of the project indicated the extent of past work and emphasized the relative

dominance of certain areas. Work had concentrated on the Wolds, due to

the large number of upstanding field monuments, while the Moors provided

a major centre for palynological studies. The Vale of Pickering was dramatically

defined by the apparent paucity of archaeological evidence. Until the late

1970's and early 1980's it remained almost entirely unexamined from the

air or the ground. Even the major discoveries at Star Carr and Flixton

Carr failed to generate a large scale program of fieldwork (although see

Schadla-Hall). While the evidence pertaining to the prehistoric occupation

of Eastern Yorkshire dramatically demonstrates the importance of the area,

it is clear that the evidence is almost entirely confined to that gained

from sepulchral deposits. The detailed evidence of settlement and economy

that would help us to understand the dead populations has been neglected

to an almost exclusive degree. Evidence recorded by 19th Century

fieldworkers and more recently by Manby, show that the chalk areas have

suffered severe erosion by both natural and human agencies from a very

early date (Manby 1975). With the exception of some major sites such as

Thwing, Garton/Wetwang Slacks and Staple Howe, it consists of nothing more

than isolated pits. The potential for the recovery of a comprehensive range

of prehistoric and later evidence on the Wolds is limited by a number of

irredeemable factors. With the exception of small isolated deposits sealed

by surviving earthworks or colluvium, the vast majority of the evidence

has been swept away.

A considerable body of work has been carried out in Heslerton

Parish over the past 150 years. Recorded work began with Canon Greenwell's

identification of a long barrow at Heslerton Wold, which he described as

having been "entirely destroyed" in 1868 (Greenwell 1877). This was probably

that excavated by the Vatchers, though this, The East Heslerton Long Barrow,

still survives as a very slight earthwork (Vatcher and Vatcher 1965). It

proved to be typical of the Yorkshire series of cremation long barrows.

Greenwell also examined three round barrows in the parish (Greenwell barrows

IV, V and VI). Barrow VI produced a number of features which are typical

elements of the Yorkshire cremation long barrow tradition, namely a facade

bedding-trench and a ritual pit, as well as a quantity of Neolithic pottery.

The two other barrows showed a high degree of organic preservation with

seeds recorded in barrow IV and what Greenwell thought to be preserved

leather in barrow V. A prehistoric burial accompanied by a jet necklace

of Food Vessel type was located within the confines of West Heslerton (Site

1) and recorded by Brewster (pers comm) in 1968. Brewster's work,

both as a teacher running one of the first field-walking programmes in

this country and as an excavator introducing the local population to archaeology

in its widest sense, laid the foundations upon which the current project

is based. His identification and excavation of the two pallisaded enclosures

at Staple Howe (in the adjacent parish of Scampston) and at Devil's Hill,

located on a knoll on the Wold escarpment, represent an important aspect

of Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age occupation in the area and the North

of England as a whole (Brewster 1963; 1981). A high degree of local understanding,

as encouraged in this case by Brewster, is essential for the success of

a broad-based landscape research project.

Geomorphology of the Parish

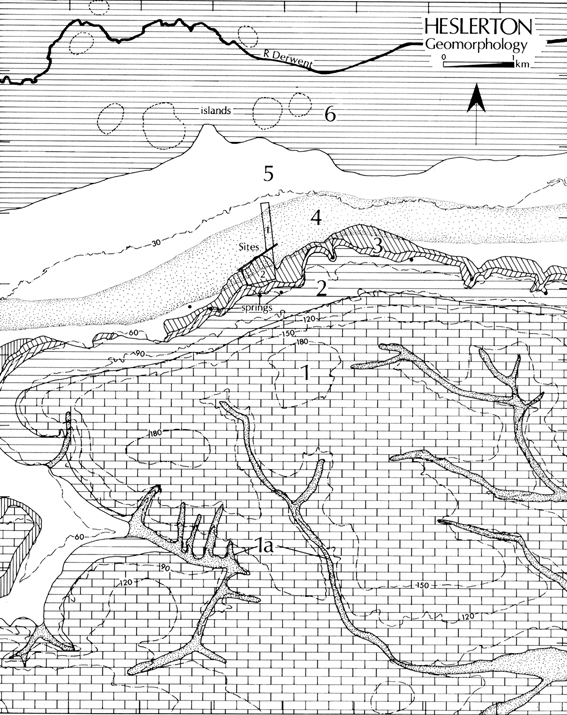

Figure 3 Geomorphology of the Parish Project area (after

Powlesland et al, Arch J, 143 (1986) page 57)

For the purposes of the project the small parish of Yedingham

(which includes the remains of a Benedictine Abbey) has been included in

the scheme; it is almost entirely enclosed by the boundary of Heslerton

parish to the south and by the river Derwent to the north. It was decided

to look at an area 10km by 10km square, with Heslerton parish in the centre

of the area. It was felt that this area would allow for the development

of the parish to be set firmly in its position in the evolution of the

landscape. The project design for research into the development of a landscape

presupposes a number of assumptions. Firstly that there is a direct relationship

between human activity and the geomorphology of a given area, a situation

which certainly existed before the Medieval period when continuous control

of the environment took place. Secondly that parallel zones of geomorphology

and environment will also reflect a similar past thereby enabling the data

recovered to be extrapolated to a wider area. These assumptions accepted

it would seem to be essential to first examine and define the differing

geomorphological zones present in the parish. In simple terms the parish,

which covers an area of circa 26.5 square kilometers, encompasses roughly

equal areas of the Yorkshire Wolds (dry upland) and the Vale of Pickering

(wet lowland). On more detailed examination these two areas can be broken

down into six distinct zones which form the landscape entities as defined

by geology, relief, drainage and to a certain extent micro-climate, as

well as the archaeological evidence of past activity.

Zone One - The Wold Top

The largest zone comprises an area of open chalk downland.

It is defined to the north by the 150m contour and elsewhere by dry valleys

containing extensive deposits of alluvial sands and gravels frequently

capped by colluvium (Zone 1A). The archaeology of this zone is most dramatically

demonstrated by the upstanding monuments, the ditch and bank systems (the

Wold Entrenchments) and the barrows. The extent of modern erosion is indicated

by the wealth of levelled crop mark sites of similar features. Only beneath

the upstanding earthworks or beneath colluvial deposits in the dry valleys

is any stratigraphy likely to have survived, though important environmental

deposits must be preserved beneath the banks of the Entrenchments. Though

this system of major boundary works has clearly had an influence on the

land division of the chalk areas for a very long period of time, they remain

an enigma having been the subject of only minimal examination.

Zone Two - The Wold Scarp

This zone, contained by the 150m and 90m contours, incorporates

the steep, north facing scarp of the Wolds, where the steep incline has

restricted the development and build up of fertile soils. That this zone

is of considerable archaeological importance, despite the restrictions

imposed by local geography, is demonstrated by the situation of two important

Late Bronze/Early Iron Age pallisaded enclosures on steep-sided knolls

within this zone, at Staple Howe and Devil's Hill. Similar sites can be

postulated at regular intervals both to the east and to the west.

Zone Three - The Wold Foot

This zone spans the basal red chalk and the Speeton clay

deposits, and is located between the 90m and 50m contours. The presence

of the spring line at the junction of the chalk and the clay gives the

zone a particularly high potential. Both the present day villages of East

and West Heslerton are centered in this zone. A number of buried or relict

stream channels are indicated by aerial photography of the area.

Zone Four - The Aeolian Deposits

Zone four was defined by the rescue excavations of 1977-1985

(Heslerton sites 1 and 2), and consists of areas of windblown sand, which

serve to conceal and protect old ground surfaces and structural remains,

in places with up to a depth of three metres. The blown sands, which are

derived from a much more extensive deposit of post glacial sands and gravels

beneath them and to the north, have been accumulating since the late Neolithic

period at least, though the mechanics of the process over time are far

from perfectly understood. The process continues today, as seen in the

photograph above, taken in March, 1998. Crop mark evidence is here unreliable,

due to the great depth of overburden, while field walking cannot hope to

give details of activity sealed well below the plough soil. Remote sensing

and geophysical surveying can give reliable results when the windblown

sand cover is restricted to depths of less than and up to a metre, but

for the deeper deposits only chance discovery during destruction coupled

with intensive fieldwork can be used to assess the full potential of the

sealed deposits.

Zone Five - The Dry Vale

An area of post glacial sand and gravel, zone five is bounded

to the south by the overlying aeolian sand deposits and to the north by

the lacustrine clays of zone six. Crop mark evidence indicates that this

area of light soils experienced the same level of activity recognizable

in zone four, and suggest that they cover a number of periods. Central

to this zone is a continuous series of ladder settlements and field systems

(of late Iron Age/Romano British date) which can be traced for circa 15km

along the 27 to 30m contour lines in the southern part of the Vale. There

is a corresponding ladder settlement in the northern part of the Vale,

although this settlement is not so well attested by the aerial photographic

evidence. Possible gaps in the aerial photographic record may indicate

particularly well preserved areas of the settlement, covered by aeolian

deposits, while particularly well-defined areas, where even individual

hut circles can be identified, may prove to be the most seriously damaged

by modern agricultural methods.

Zone six - The Wet Vale

Zone six incorporates the small parish of Yedingham, and

comprises a large flat area of lacustrine clays, frequently cut by relict,

and now peat filled stream channels, and including a number of slightly

elevated gravel islands. Although Zone six would have supported a fenland

environment during the later prehistoric period, successive drainage schemes,

particularly during this century, have dried out the greater part of the

area, in order to facilitate the present intensive arable farming.

Methodology - The Parish Transect

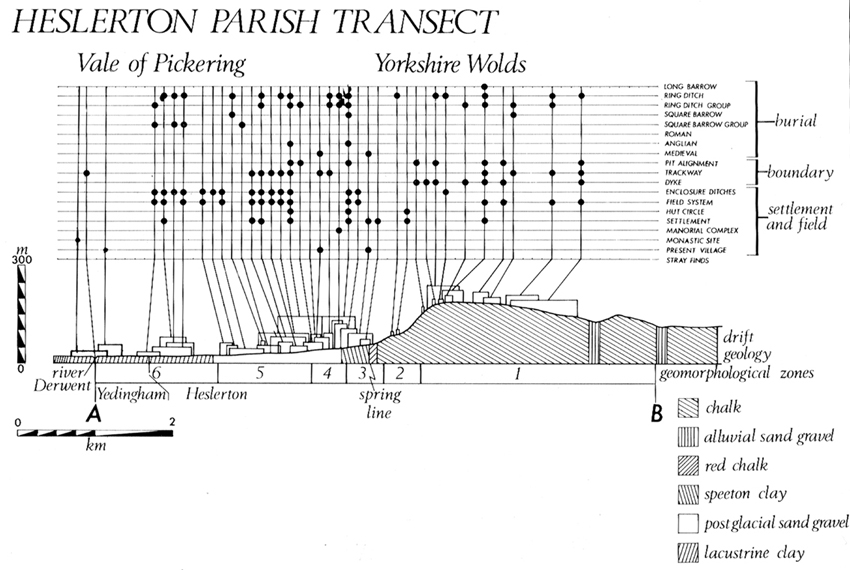

Figure 4 The Parish Transect (after Powlesland et al,

Arch J, 143 (1986) page 58)

The analytical model upon which the project is focused

is the Parish Transect. This brings together the different factors of geomorphology

and archaeology and cuts across the "grain" of the landscape at right angles.

The raw data with which the project began consisted of aerial photographic

plots combined with a limited amount of fieldwork plotted against the geomorphology.

The purpose of the project was to refine this working model by more detailed

examination of all the potential sources of evidence in order to develop

a detailed understanding of the landscape in both spatial and chronological

terms. The excavations at Heslerton have clearly indicated the potential

for developing the model to expand our knowledge of the complex socio-economic,

climatic and geomorphological factors and their inter-relationship in the

evolving landscape. By the selective application of similarly detailed

analysis of the other geomorphological zones in the parish it should be

possible to expand the knowledge to a degree which would have major implications

for the understanding of an important archaeological region.

Methods and Resources

In order to understand the development and evolution of a

landscape, even when this study is limited to a 10km by 10km square, the

widest range of methods must be applied. As well as using the tried and

tested methods, the Heslerton Parish Project has been at the forefront

of developing new techniques in excavation as well as assessing different

methods of remote sensing and their possible applications to an archaeological

understanding of the landscape.

Aerial Photography

The aerial photographic programme continued on an intensive

basis up till 1984, by which time it was felt that nothing less than a

massive increase in flying time, or a change in agricultural methods, would

substantially increase the number of known sites. A number of high resolution

colour vertical photographs of the area were obtained by the NERC during

June 1992, a particularly good year for the development of cropmarks, and

these enhanced the number of sites, although more often providing greater

detail of known sites.

Preliminary tests indicated that soil conditions in the parish

were conducive to the application of geophysical prospecting techniques.

This has since been proven on a number of the different geomorphological

zones, with results ranging from average to excellent. It is planned that

further geophysical surveying will take place at regular intervals, both

to enhance the known archaeology and to investigate the apparent "blank"

areas in the coverage.

The project also pioneered the use of high

resolution geophysics after the removal of the plough soil, which,

allowing for the already proven high magnetic susceptibility of the site,

produced some spectacular results.

Environmental Survey

It was considered that the undertaking of an environmental

survey was of prime importance. A detailed examination of the environmental

deposits, whether preserved in peat or beneath earthworks, would have significance

for the region as a whole, perhaps allowing sites examined in the parish

to be tied in and compared with others in the region, both on the Wolds

and on the Moors. The survey was to have included the preparation of detailed

soils maps, the sampling and identification of the areas of greatest environmental

potential within each geomorphological zone and the identification of threats

to environmental deposits by agricultural or other agencies.

Documentary Survey

Initial documentary work was carried out, which proved that

by the time of the Domesday survey, the current position with two villages

(West and East Heslerton) was already in place (Eslerton and the Other

Eslerton). By the 17th Century the villages were known as Great

and Little Heslerton. A number of medieval earthworks, a monastic and a

manorial site are known in the parish, all of which should prove of importance

as further documentary work is to be carried out in the near future.

Remote Sensing

Remote sensing, in its widest possible context, can be defined

as being the attempt to gather data or evidence using non-invasive techniques.

For our purposes, we will deal with geophysical surveying under a separate

heading, reserving remote sensing for the aerial or satellite gathering

of data. While not part of the original project objectives, developments

in the field of remote sensing soon made it apparent that these techniques

could be of use to the archaeologist. The project, through academic links

with the Department of Geography, Durham, was able to acquire both a SPOT

image and a multi-spectral image (acquired by the NERC) covering the project

area. Analysis of the images is ongoing, but the initial results prove

the great potential of remote sensing as a powerful tool for the archaeologist.

Excavation

A total of approximately 19 hectares were excavated at West

Heslerton between 1977 and 1995.

Field Walking

A field walking programme was to be initiated to provide

evidence of date, function and damage to known cropmark sites. It was also

proposed that apparent negative areas be investigated, as experience had

shown that this view could be highly misleading.

Bibliography needed

Brewster

Manby

Longworth (1961)

Simpson (1968)

Clarke (1970)

Cunliffe (1974)

Rahtz, Dickinson, Watts (1980)

Prehistoric Society (1978)

Greenwell, W. and Rolleston, G. 1877, British Barrows, Oxford.

Mortimer, J.R. 1905, Forty Years Researches in British and Saxon

Burial Mounds of East Yorkshire, London